Bollywood라이브 바카라 love affair with the item song is as old as commercial Indian cinema itself. From the smoky cabaret performances of the 1960s (dotted with burlesque and jazz influences) to the aggressively choreographed club bangers of today, these songs have been one of the most consistent elements of our cinema. Even as these catchy songs—with their provocative imagery and lyrics—evolved, they routinely commodified and reinforced the sexualisation of women. Long before we had the vocabulary of the internet—before 'incels' became an easily recognisable subculture of lonely, regressive men—Bollywood was already in on the game, manufacturing desire through the cinematic lens.

Incel Culture & Item Songs: Misogyny In Music, Bollywood And Beyond

Long before 'incels' became an easily recognisable subculture of lonely, regressive men, Bollywood was already in on the game with the item song, manufacturing desire through the cinematic lens.

There is no denying that some of the greatest dance tracks in Bollywood have been item songs. They are popular, hypnotic, and have cultural staying power. You may forget the film but you will remember the music. With ‘Kajra Re’ (Bunty Aur Babli, 2005) or even the more folksy dance number ‘Chaiyya Chaiyya’ (Dil Se.., 1998), the aesthetic sensibilities of the lighting or choreography alone could keep you captivated for hours.

Helen (as well as Bindu) became a silver screen icon by fronting numbers like ‘Aa Jaane Jaan’ (Intaqam, 1969) and ‘Piya Tu Ab To Aaja’ (Caravan, 1971). While these songs spoke of female lust and desire in empowering ways that the traditional songs featuring the “good girl” heroines couldn’t, the item songs or dance numbers today are a whole different beast. The Madonna-whore dichotomy was strong in Hindi cinema of yore, where the 'good' woman is the one to be married, and the 'bad' one existed to dance for your pleasure. Over the years, the lines have blurred, and many of these item songs are performed by women who also play the demure heroines.

Nowadays, the goal is simple with item songs: push a film라이브 바카라 visibility, give influencers a hook to recreate endless promotional content, and most importantly, give the audience something to gawk at. What once served narrative functions [like ‘Mehbooba Mehbooba’ in Sholay (1975)] is now just a marketing tool. A hypersexualised party song in the end credits does the job, even if it라이브 바카라 poorly choreographed or unimaginatively produced, like ‘Dabidi Dibidi’ (Daaku Maharaaj, 2025).

Feminist readings of item songs do have merit, but the truth remains that the women are the objects of desire in these songs, not the men. We would not have an awkward Tripti Dimri thrusting and gyrating on the floor nonsensically in ‘Mere Mehboob’ (Vicky Vidya Ka Woh Wala Video, 2024) otherwise.

The key problem is not the existence of sexuality in these songs. Cinema has always found ways to seduce. The problem is the structural imbalance. Female desire is rarely given the same weight in these songs. When it is done in films like Aiyyaa (2012) with songs like ‘Dreamum Wakeupum’ or ‘Aga Bai,’ they rarely ever reach the same iconic status in our pop culture consciousness. The audience rejects it because the woman being in charge no longer satisfies the male fantasies of controlling and dominating female sexuality.

Bollywood's item songs oscillate between outright objectification and performance art. Songs like ‘Zaban Pe Laga Namak Ishq Ka’ (Omkara, 2006) tapped into something primal. Meanwhile, ‘Sheila Ki Jawani’ (Tees Maar Khan, 2010) was self-aware in its sexual bravado, with Katrina Kaif singing about her own desirability in a way that felt almost like a power move.

However, most item songs tell us, in no uncertain terms, what kind of female body is worthy of longing and obsession. There라이브 바카라 a pattern to framing the women in item songs—the bare skin of the woman shines as the camera slowly pans across her seductive eyes, heaving chest, and undulating hips. They encourage a certain mode of looking—a gaze that lingers and reduces women to mere moving parts. It is a carefully curated aesthetic. It feeds directly into the voyeuristic desires of an audience conditioned to see women not as empowered performers but as sexualised spectacles.

The male gaze in item songs often pivots to slut-shaming tropes, framing boldness as moral transgression. When Badshah laments “Aur kitni tareefan chahidi ae tenu” in ‘Tareefan’ (Veere di Wedding, 2018), it doesn’t uplift—it echoes the incel-fueled 80-20 myth, that 80 percent of women desire only the top 20 percent of men so they need to be manipulated. It encourages the narrative that women are too demanding and must be manoeuvred into lowering their standards. When he sings, “Baby god damn tu hai 100, baaki average,” he pits one woman against another.

The line “Main to tandoori murgi hoon yaar, gatkaa le saiyyan alcohol se” (translated: I am a tandoor chicken, swallow me with alcohol, oh my beloved) from ‘Fevicol Se’ (Dabangg 2, 2012) feeds directly into incel ideologies by reinforcing the idea that women are objects to be devoured and discarded. This is exactly the kind of dehumanising rhetoric that patriarchy thrives on, where female autonomy and desire are irrelevant, and women exist solely for male consumption—whether he is an alpha male or an incel.

While shooting the song ‘Beedi Jalai Le’ (Omkara, 2006), Bipasha Basu reportedly felt overwhelmed and intimidated by the sheer number of male background dancers surrounding her on set. The discomfort was so intense that she momentarily fled the shoot. Observing her distress, co-star Saif Ali Khan stepped in to calm her down and Basu was able to regroup and complete the performance. If anything, this incident highlights how even the women performing in these sexualised numbers are often made uncomfortable by the very gaze they are catering to.

Down South: The Cult of the Navel

If Bollywood has a long history of objectification, South Indian cinema has perfected it. Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada films have historically been the biggest propagators of the navel-gaze (both literally and metaphorically). The camera work in these films is almost obsessive in how it zooms, pans, and fixates.

Watch any mainstream Telugu film from the late ‘90s and early 2000s, and you’ll see a formula: a heroine, often introduced through a slow-motion waist shot, her body fragmented before her face is even revealed. This fragmented way of looking is present even in regular songs like ‘Dhivara’ and ‘Pacha Bottasi’ (Baahubali: The Beginning, 2015). In contrast, ‘Mamatala Talli’ presents Ramya Krishna라이브 바카라 Sivagami in full, suggesting that motherhood renders her ‘worthy’ of a more respectful gaze.

There is a reason why the navel is almost fetishised in Indian cinema. Unlike in the West, where cleavage might be the focal point of sexual allure, Indian cinema—especially in the South—has built an entire erotic lexicon around the midriff. From the drenched sarees of the 1980s to the cropped blouses of the 1990s, the navel shot—a substitute for what is further down below—is the money shot.

The Subversion of the Gaze

Every generation has had to deal with moral outrage about these kinds of songs. ‘Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai’ (Khal Nayak, 1993) is veritably tame by today라이브 바카라 standards but it was once termed vulgar, inappropriate, and was even debated in Parliament. Dixit, the face of the song, wasn’t simply an object of lust; she was an active participant in the seduction. Her expressions, the classical dance influences, and the sheer theatricality of the performance elevated the song beyond mere titillation. Still, there is no mistaking whose fantasies the calculated striptease was ultimately designed to gratify.

‘Oo Antava,’ Samantha Ruth Prabhu라이브 바카라 item number in Pushpa: The Rise (2021), is a rare instance of a contemporary item song that actively critiques its audience. The lyrics directly call out male hypocrisy—men who judge women in public but desire them in private. The song attempts to turn the gaze back onto its consumers, making them uncomfortable with their own voyeurism. But the picturisation doesn’t fully commit to this reversal. While the messaging is radical, the visual language remains the same—Samantha is still sexualised, still shot through the same aesthetic prism as all item girls before her.

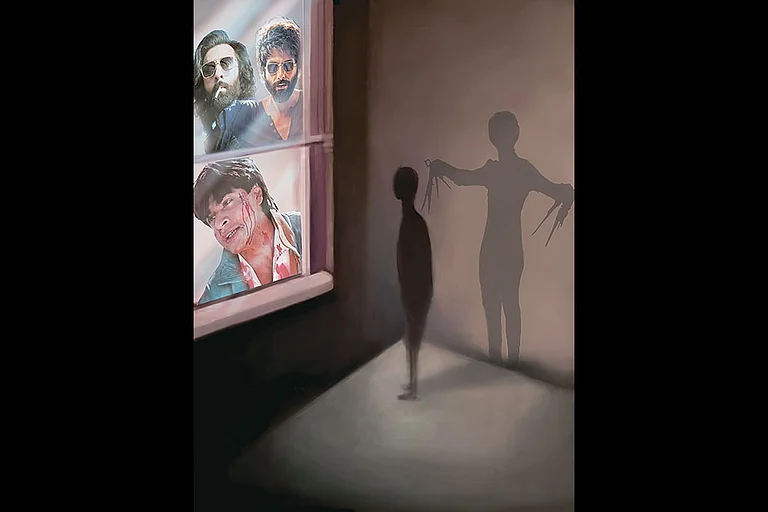

There have been moments where Bollywood has gender-swapped the gaze. ‘Dard-e-Disco’ (Om Shanti Om, 2007) was one of the first mainstream item numbers to deliberately turn the camera onto the male body. Shah Rukh Khan, chiseled and dripping, was framed in the exact same manner as women usually are—lingering shots of his abs, the water cascading down his torso, the deliberate objectification of the male physique. More recently, ‘Besharam Rang’ (Pathaan, 2023) attempted a similar double-gaze, positioning Deepika Padukone and Shah Rukh Khan as equal participants in desire. But these are exceptions, not the norm.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Many don’t see item songs as worthy of deeper critiques. But this casual complicity makes people more vulnerable to red pill ideologies that glorify trad wife aesthetics and dismiss films like Mrs. (2024) or The Great Indian Kitchen (2021) as exaggerated instead of reflective.

Having said that, item songs are not going anywhere. They are deeply embedded in the commercial DNA of Bollywood. But what needs to change is the way we frame and discuss them. Sexuality on screen is not inherently problematic—it is the imbalance, the one-sided nature of its depiction. The future of Bollywood라이브 바카라 dance numbers doesn’t have to be a moralistic retreat into prudishness. It can, instead, be a conscious re-examination of who gets to be desirable, who gets to look, and who is being looked at.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power