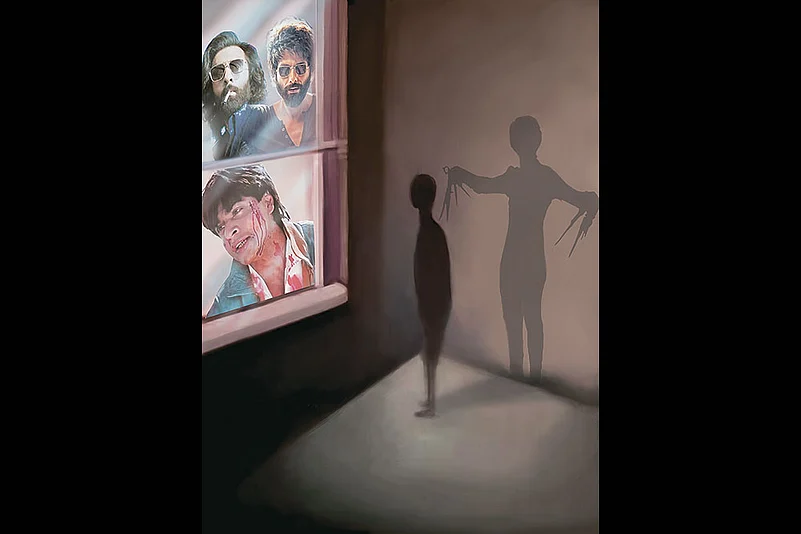

“Pehle Payal ko pata, fir hata sawan ki ghata,” (Woo Payal first and then dump her when you are done) Rocky advises a barely post-pubescent Rajiv in Ishq Vishk (2003) when he has an ardent dilemma: he does not have someone to hook up with on his freshman college trip. Amrita Rao라이브 바카라 Payal Mehra is straight-up out of the Sooraj Barjatya universe: she is simple, she is sanskaari, and Shahid Kapoor라이브 바카라 Rajiv knows that all too well. But the ghost of Kabir Singh라이브 바카라 (2019) past lurking in Rajiv라이브 바카라 psyche convinces him to manipulate Payal nonetheless.

In Ishq Vishk, Rajiv라이브 바카라 bildungsroman arc is disturbingly shaped through both emotional and physical violence upon Payal라이브 바카라 body, mind and soul. When he tries to force himself on her, she rejects him. And Rajiv promptly takes a leaf out of the incel textbook and insults Payal. He calls her a “behenji” who should have felt honoured to be desired by him. However, long before Rajiv learnt to crawl through the toxic sewers of deranged masculinity, Bollywood had already laid the groundwork for normalising such behaviour in the guise of romance.

One of Shah Rukh Khan라이브 바카라 most problematic Rahuls (an achievement of sorts) crooned, “Tu haan kar ya na kar, tu hai meri Kiran,” (Whether you say yes or no, you are mine Kiran) in the 1993 film Darr and sent shivers down an unsettled Kiran라이브 바카라 (Juhi Chawla) spine. The psychological thriller hit the nail on the head about how obsession, stalking, harassment, and a man라이브 바카라 inability to take rejection is not at all romantic but downright terrifying. But after the massive success of Darr, the audiences sympathised more with Rahul, not the hero who saved the heroine—a fact that Sunny Deol was not too happy about.

Movies like Darr, Baazigar (1993), Anjaam (1994) were game-changers in 1990s Bollywood, when courtship had already become synonymous with coercion. From Aradhana (1969) and Sholay (1975) to Dil (1990) and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), the message had been consistent: if a man just tries hard enough, the woman will be impressed. Her initial rejection isn’t her final word; it라이브 바카라 a negotiation. “Haseena maan jayegi” (literally, “the beauty will eventually say yes”) has not been a subplot but the very foundation of nearly every mainstream romantic film for decades. This has been the bedrock of David Dhawan라이브 바카라 entire filmography. From Aamir Khan to Akshay Kumar, they have all been guilty of perpetrating this trope.

In such a scenario, where the ideas of basic consent are deemed redundant, conversations about enthusiastic consent—explored in Pink (2016)—have no space. This is why many viewers struggle to recognise films like The Great Indian Kitchen (2021) or its remake Mrs. (2024) as portrayals of marital rape, brushing them off as mere depictions of ‘bad sex’. It라이브 바카라 also why they fail to connect the dots between on-screen entitlement and real-life violence—the one depicted in Chhapaak (2020), where Deepika Padukone라이브 바카라 Malti becomes an acid-attack survivor. Malti라이브 바카라 story, based on Laxmi Agarwal, reflects a brutal truth: Laxmi was a minor, just 15, when a 32-year-old man, Naeem Khan, threw acid on her face for rejecting his advances—a horrific consequence of male entitlement to women라이브 바카라 bodies.

The Incel Culture

Adolescence (2025) has sparked a much-needed debate about incel culture and manosphere across the globe. Even in India, everyone from media outlets to millennial parents are raising concerns about helping young men navigate a life where incel influencers like Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate are more easily accessible than ever before. The likes of Carry Minati, Ranveer Allahbadia, Elvish Yadav and Samay Raina have taken up the mantle closer home to condition young men in the language of toxic masculinity. It라이브 바카라 impossible to ignore how these ideologies are shaping young minds today.

Adolescence dives into the life of a young boy, Jamie Miller, who gets pulled into the toxic orbit of online bullying. The show excavates how his anger from feeling rejected ultimately leads to the loss of a life. Much of the story is rooted in the rhetoric of modern-day incels. This show is unflinching in its portrayal of how young men are socialised to feel entitled to women라이브 바카라 attention and affection, and yet, what라이브 바카라 ironic is that Adolescence isn’t exactly breaking new ground. These ideas were seeded much earlier, especially in India and, by extension, its populist cinema. Long before the terms “incel” and “manosphere” were even part of the cultural lexicon. When Aman said: “Chhe din, ladki in” (Six days and the girl will give in) in Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003), it wasn’t a joke, it was the playbook.

Blueprint for Manosphere

Bollywood has been selling the idea that a woman라이브 바카라 “no” is just a challenge for the hero to overcome for nearly a century now. Some of it is a reflection of patriarchal sentiments while some of it actively goes on to shape it. And all is deemed good because the hero gets the girl at the end anyway. From the golden age of Hindi cinema to the era of pan-Indian blockbusters, Indian films have consistently romanticised the disturbing idea: “Uske na mein bhi haan hai” (There라이브 바카라 a yes even in her no).

From obsessive lovers rebranded as romantic heroes to stalking framed as sincerity, our cinema has normalised entitlement.

In Bollywood, the trope took root early. Films like Junglee (1961) and Aradhana (1969) showcased the romantic hero as a gentle stalker, wooing women who initially resist. But the trope solidified in the 1970s and 80s, with larger-than-life male leads who treated rejection as foreplay. Sholay (1975) offered a comedic spin with Dharmendra라이브 바카라 relentless pursuit of Basanti. In Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), each male protagonist wins over women through a combination of persistence, slapstick, and dominance. The 90s sealed the trope with Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), where Raj라이브 바카라 repeated boundary-pushing is framed as charming, and Simran라이브 바카라 eventual surrender is presented as inevitable.

When I was in high school, sites like Reddit and 4chan—the digital watering holes for incel rage—were not yet popular in India. Yet, that sickening incel mentality was already deeply rooted in our psyches. I was chastised by another girl for saying no to her friend despite him asking me out multiple times. Him stalking me and sitting outside my classroom should have charmed me, she had said. “Who did I think I was?” she had asked. When my best friend was pursued by another guy for years, despite her repeated rejections, everyone else—our friends and peers—believed she would give in eventually. It was inevitable, they proclaimed. “She simply didn’t yet know she wanted it too.”

This is the coda Bollywood has been promoting as romance for decades. It라이브 바카라 a pattern that mirrors the entitlement seen in today라이브 바카라 incel culture. This framework has become so entrenched that it often transcends genre. In action films, romantic subplots still relied on coercive flirtation (Dabangg (2012), Rowdy Rathore (2012)), while even supposed “rom-coms” used manipulation as the love language (Humpty Sharma Ki Dulhania (2014), Badrinath Ki Dulhania (2017)). At its worst, the trope enables outright harassment. At its best, it dictates that women should do the emotional heavy lifting and teach their men about equality and respect. However, the bottom line remains that “true love” involves stalking, emotional blackmail, and even physical aggression—because the man knows better than the woman what she really wants.

This toxic narrative isn’t confined to Bollywood alone. Even South Indian cinema isn’t immune. Take Baahubali: The Beginning (2015), where the hero, Shivudu (Prabhas), through sheer force of will, strips away Avantika라이브 바카라 armour both literally and metaphorically. He “conquers” her, not by respecting her autonomy, but by taming her. The existence of this gaze is also ironic in a story where Shivudu라이브 바카라 father Amarendra Baahubali caused an entire civil war after chopping off the head of the man who threatened to touch his wife Devasena inappropriately. Baahubali serves as a compelling case study in how the morality of actions is often determined by the identity of the one performing them.

The lines between romance and harassment are blurred deliberately. This helps position men as saviours when they are the perpetrators themselves. The hero and the villain get to fight over a woman라이브 바카라 body as if it라이브 바카라 their territory to claim. With consent often subordinated to the hero라이브 바카라 status, rather than the nature of his actions, our fiction keeps repeating that if he라이브 바카라 the lead, he라이브 바카라 entitled; if you’re the object of his desire you have no choice. From Tere Naam (2003) to Arjun Reddy (2017) and its Hindi remake Kabir Singh, mainstream cinema in India and its majoritarian audience does not want to even pretend about respecting women or their autonomy.

When a film like Thappad (2020) comes along, it becomes an outlier. It becomes part of a movement that has been trying to push back. Films like Queen (2013) and Piku (2015) create a separate space where female protagonists do not need to be won over by persistence. They get to prioritise self-worth and boundaries. And stories like The Lunchbox (2013) get to depict love as a space of emotional honesty.

The internet may have given incels a louder microphone, but Bollywood handed them the script decades ago. From obsessive lovers rebranded as romantic heroes to stalking framed as sincerity, our cinema has normalised entitlement and celebrated male desire as destiny. The rise of incel culture in India is simply the inevitable evolution of a mindset that has always existed in a patriarchal system. Until our stories start valuing consent as clearly as they glorify conquest, we’ll keep raising generations that confuse love with control—and call it romance.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power

This article is part of 바카라라이브 바카라 April 21, 2025 issue 'Adolescence' which looks at the forces shaping teenage boys today—online misogyny, incel forums, bullying, and the chaos of the manosphere. It appeared in print as 'Haseena Man Jaayegi'.