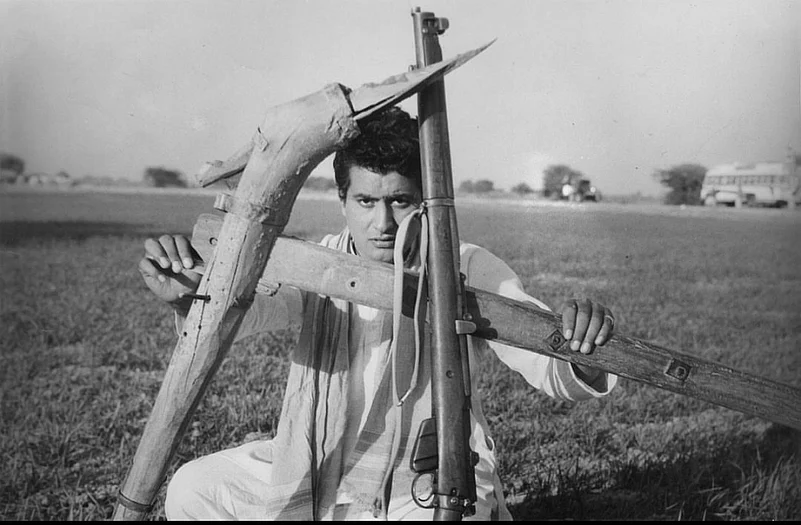

One of the most memorable images in Hindi cinema, which has represented the working class and farmers, has been the shot of a plough and a rifle against a blue sky from Upkar (1967)—symbolic of Lal Bahadur Shastri라이브 바카라 slogan ‘Jai Jawan Jai Kisan’. The slogan is an ode to the love, unimaginable efforts, undying work and commitment of the farmers in growing the grain and the sacrifices of soldiers in keeping the borders safe. It라이브 바카라 an idiom used to measure levels of patriotism in common conversation till date (politicised by the current government to hide its inadequacies and mute those questioning it). Upkar was made post the 1965 war and charted the hero라이브 바카라 journey of being a farmer and a soldier and his sacrifices and love for the nation. It also threw light on the growing corruption, and consequently, the disillusionment with oppressive systems—systems born out of class differences, black market creations and ambitions. The rise of capitalistic desires was prevalent and identified as an enemy. The other enemies were personal ambitions—as opposed to collective growth—and temptations with ‘western’, rich lifestyles.

It was this idea of a collective—the idea of working-class India progressing together on the path illuminated by Gandhi, Nehru and the dream that was seen during India라이브 바카라 independence—that was brought to life in Upkar and many films that came to be identified with Manoj Kumar라이브 바카라 filmography in Hindi cinema.

It is true that Manoj Kumar goes beyond being ‘Bharat’ in highly successful and memorable films that punctuate his career from the beginning to the end, ranging from Hariyali aur Raasta (1962), Woh Kaun Thi (1964), to Patthar ke Sanam (1967) and many more. However, it is also true that ‘Bharat’ has been his most identifiable character, and his most critical contribution to the landscape of Hindi cinema. ‘Bharat’ embodied love for the nation with constructive acts. He was a patriot with a beating heart. He held the culture and ethos of the nation as close as the ideas of togetherness and helping one another. The leader of the collective, he was one of the voices of the oppressed—which was the majority of the population. Unafraid to call out the oppressors, unafraid to challenge the ‘westerners’, and remind the world of the contributions and supremacy of India in culture, heritage and so much more.

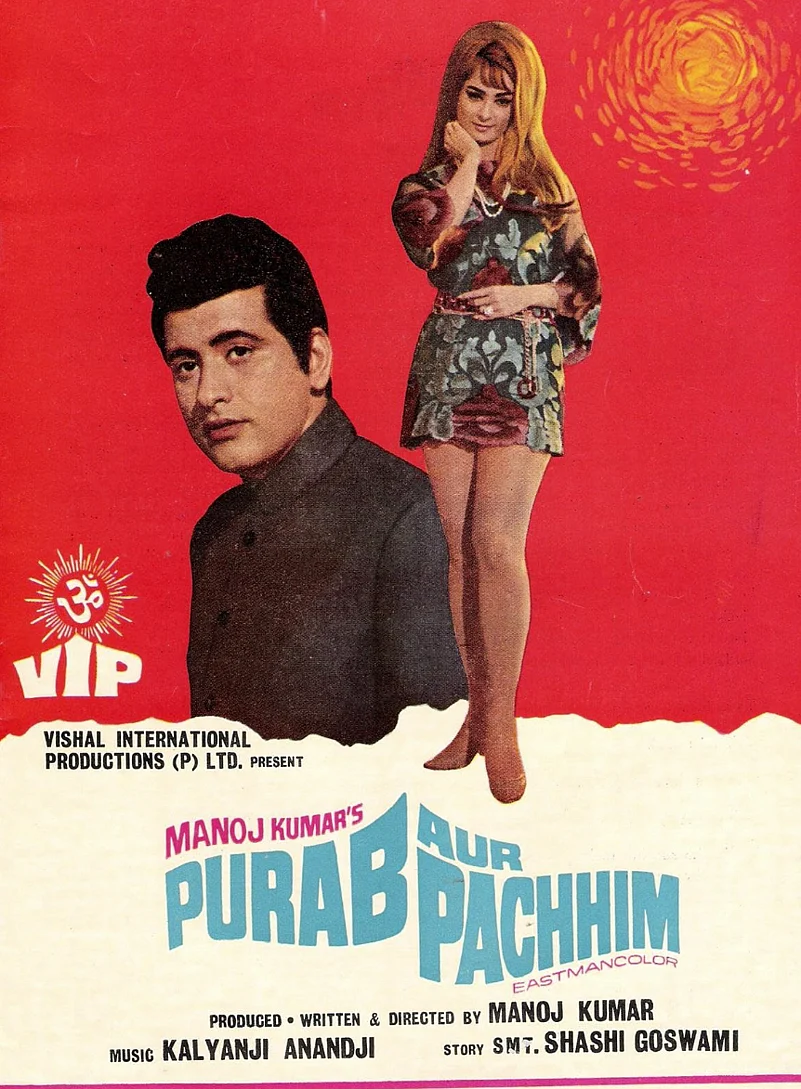

The journey that began with Shaheed (1965), was followed by Upkar, Purab aur Pachhim (1970), Roti Kapada aur Makaan (1974) and Kranti (1981). Even Himalaya Ki God Mein (1965) can be categorised under a similar genre, keeping in mind the role of the protagonist, as he played a doctor who worked in a remote village. His allegiance to the messages of unity that the government wished to convey was clear. However, so was his allegiance to the working class in these films. And that is where his presence in cinema becomes important. In Roti, Kapada aur Makaan (1974)—the title itself born from the bare necessities that everyone should have—the song ‘Mehengai maar gayi’ becomes crucial. It is a song of the poor critiquing how difficult life is in the ever-increasing prices—the constant pressure of life, while rich live in comfort and the poor struggle for basics. This theme has been eclipsed from popular Hindi cinema post liberalisation, much like the working class has been made to disappear from its narratives. Songs around class disparities and issues of ‘mehengai’ (economic inflation) have only emerged in films like Peepli Live (2010) with ‘Mehengai daayan’ and Article 15 (2019) ‘Dhak se’—a popular song of protest used in the film.

What is also important to note is that all of Manoj Kumar라이브 바카라 patriotic films were not of a single color. While one looked at the socialist revolutionary Bhagat Singh, the other was a commentary on the basic necessities required to lead a life. While one was about restoring ‘respect’ in the idea of India both from a perspective of the east and west, and attempting to elevate India as culturally supreme, the other looked at the contributions of both farmers and soldiers in keeping India both functional and safe. However, what was common in each of the films was the fervour and the spirit of patriotism—the sense of irrational love for the nation that is paraded even today and often used conveniently in political conversations to substantiate dubious claims and cover failures.

This infusion of nationalistic pride is possibly Manoj Kumar라이브 바카라 greatest contribution to popular Hindi cinema and Hindi film music. Even today, on occasions when India remembers its allegiance to the nation and needs to display it in full glory, one sees the reliance on evergreen Manoj Kumar film songs, which are incomparable when it comes to this sentiment. These songs were devoid of the critique and socialist commentary seen in Raj Kapoor라이브 바카라 films, or in Guru Dutt라이브 바카라 Pyaasa (1957), but eulogised the nation and the sheer love for it. ‘Mere desh ki dharti’ from Upkar, ‘Jab Zero diya mere Bharat ne’ from Purab aur Pachhim, ‘Mera rang de basanti chola’ from Shaheed, ‘Kranti kranti’ from Kranti’ are a few examples of songs that have etched themselves in public memory every time patriotic display is needed.

And that is what Manoj Kumar films also did—they legitimised the display of love for the country. However, each of his films was embedded in a social-political-economic reality of the time, vocalising the concerns and angst of the oppressed and the working class. The biggest disservice generations after have done to his cinema and music from his films is divesting the narratives and songs from those contexts—looking at the idea of loving the nation in isolation, removing the active role every citizen must play in improving the nation we love. Manoj Kumar라이브 바카라 films also taught us that the actions were ours to take while displaying the love for the country—something we seem to have conveniently forgotten in the age of forgotten promises and ‘Acche Din’, from the party he later joined in his political career.