Nelson Mandela, —South Africa라이브 바카라 first Black President who spent twenty-seven years in prison for opposing brutal apartheid laws — had famously remarked “that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.”

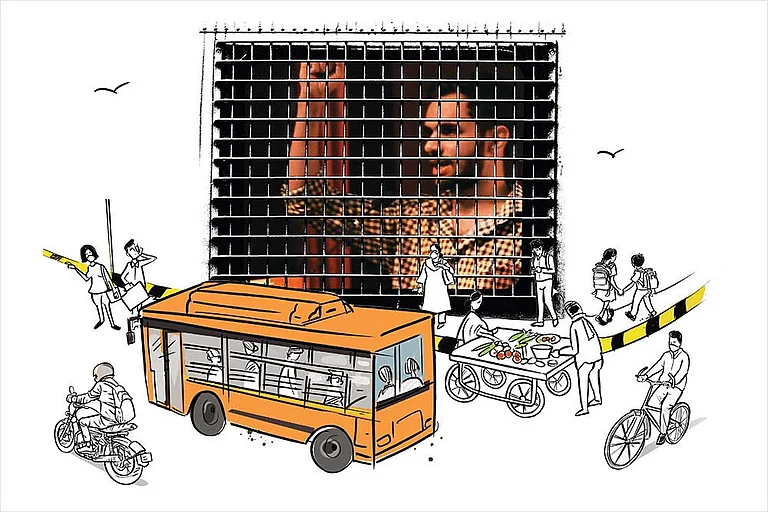

Journalist Neeta Kolhatkar attempts to do just the same with her book The Feared — Conversations With Eleven Political Prisoners, released in Mumbai this week. In meticulously documenting the harrowing jail-life experiences of prisoners charged for sedition and unlawful activities, Kolhatkar lifts the lid off the darker side of Indian democracy, and the price one pays to uphold the rights of the oppressed.

From noted human rights defenders, public intellectuals, academicians, to political leaders, lawyers and journalists, these individuals have been incarcerated for their political beliefs, activism, and dissent against the state. Each chapter narrates the appalling conditions of prisons, the psychological toll on the prisoners, the impact on their families and the discriminatory system that treats the prisoners differently based on their caste, religion and nature of crime.

The book is a collection of interviews conducted by Kolhatkar of political prisoners or as she refers to them as 'prisoners of conscience' — a term coined by British human rights activist and founder of Amnesty, Peter Beneson — who are currently out on bail or with their family members. It also features first-hand accounts of prominent convict-prisoners whose names might not be well-known, but whose stories are equally powerful.

Those who were interviewed by Kolhatkar include the accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, like lawyer Sudha Bharadwaj, scholar Anand Teltumbde, poet and activist Varavara Rao as well as his wife P. Hemalatha, and professor Shoma Sen. Rights activist Prashant Rahi, communist ideologue Kobad Ghandy, former Lok Sabha member K. Muraleedharan, medical professional and activist Dr. Binayak Sen, Shiv Sena MP and spokesperson Sanjay Raut, Sameer Khan —the son-in-law of Nationalist Congress Party (Ajit Pawar) leader Nawab Malik and Manipur journalist Kishorechandra Wangkhem also shared their accounts.

Most of these individuals were detained during the BJP라이브 바카라 tenure which began in 2014. But others like Binayak Sen, Ghandy, Muraleedharan, Rao and wife Hemalatha were accused in connection with Naxal or Maoist activities and were imprisoned during Congress rule. The UPA government between 2004–14, was the first to crack down on activists and academicians and accused them of being Naxal or Maoists sympathisers.

Sen —who worked in Chhattisgarh among the mine workers and tribals — was one of the earliest figures who was accused of being a Naxal ideologue and arrested in 2007. Ghandy, a Leftist Parsi from Mumbai was arrested in 2009 by the Delhi Police on sedition charges. Muraleedharan, editor of propaganda magazines like The Comrade and MassLine from Kerala, was first arrested during Indira Gandhi라이브 바카라 Emergency era and again in 2015. Rao was put behind bars in 1970 and 1973, and Hemalatha in 1992.

The eclectic mix of the accused shows that no matter which political party is in power or their ideology — they have resorted to suppress dissent and punish opponents critical of the government by way of long incarceration. The prolonged and harsh prison confinement is intended to not only break the mental will and physical resilience of these individuals, but also to isolate them from their activism.

It is heartening to learn that in such a bleak scenario, many kept the spirit of activism alive by bonding with their fellow inmates. In Byculla jail, Bharadwaj struggled to find any time for herself as she was busy writing applications for others. She continued the work for undertrials after getting out on bail as she received many such requests from the prison. In Navi Mumbai라이브 바카라 Taloja jail, where most of the Bhima Koregaon accused are detained, activist Arun Ferreira (not featured in the book) came to Sameer Khan라이브 바카라 help in explaining the prison rules and procedures.

Ghandy라이브 바카라 first time in the notorious Tihar jail was made easy after he bonded with an extremely helpful Afzal Guru, alleged mastermind behind the 2001 armed attack on The Indian Parliament. Muraleedharan would protest with senior authorities when any of his prison mates were beaten in Pune라이브 바카라 Yerwada Central Jail.

Undoubtedly, their ordeal worsened during the Covid-19 lockdown when jail authorities imposed stringent restrictions and suspended physical meetings with family members and lawyers. For weeks and months, the inmates spent time without any news of their loved ones. In some prisons phone calls, were allowed for only five minutes with family members. Following social distancing norms was practically impossible in the overcrowded prison cells, and many including Teltumbde, and Father Stanislaus Lourduswamy (accused in Bhima Koregaon case, popularly known as Stan Swamy) were infected with the Covid-19 virus. Medical negligence is common, and it can take between weeks to months before jail authorities take action. Swamy, 84, and Pandu Narote, 33, who was also accused of being a Maoist, both passed away following delayed medical attention.

Violation of human rights by unjust treatment and discrimination against different classes of prisoners is common in many jails. The Model Prison Manual introduced in 2016 aimed to bring parity to the prison administration and assured that it will uphold the human rights of prisoners. But many states, including Maharashtra, are yet to adopt the rules, and they still follow colonial British rules of administration. As a result, prisoners suffer in accessing basic rights like meetings and phone calls with families. Prison authorities also appear to act tough against inmates accused of being Maoist sympathisers or involved with Naxal activities upon a directive from the center. They were given separate uniforms with a green band at the edge of the sleeve of the shirt so they can be identified among others. Families of prisoners cannot send food to jails in Maharashtra. But those with access to money can buy special food like chicken on Sundays, and many use this privilege to swap barrack duties of washing, cleaning and sweeping with poor inmates.

The harsh physical conditions of incarceration and the psychological toll can break the spirit of even the most resilient individuals. The interviews reveal how the political prisoners overcame their personal struggles to keep their sanity intact. Upon discovering that the jail staff communicated only in Marathi, Bharadwaj and Muraleedharan picked up the skills to learn the language. Convict prisoners are usually allowed to carry up to 12 books, but in Yerwada jail Muraleedharan was refused when he wanted to carry books and had to request the courts for a permission for a Marathi grammar book and dictionary so he could read Marathi books in the library.

While the interviewees are out on conditional bail or acquitted, they have struggled to resume normalcy in daily lives out of prison, like getting a rented apartment, getting evicted routinely and even finding support from friends. The impact of imprisonment has particularly been adverse on their children and partners who spent weeks and months worrying about their condition and praying for their early release. But despite the severe personal struggles, they have picked up the spirit of resistance and fight for justice.

By keeping the conversations focused on the brutal realities of their imprisonment, the conditions of prisons, the sufferings of family and the cost one pays for strongly upholding ideological beliefs, Kolhatkar sheds light on the draconian state policies, and the politics that has smothered hundreds of people behind bars. The eventual acquittal of political prisoners illustrates that fake cases are built with false accusations to merely ensure they abandon their activism or stop challenging the establishment.

The conversational style of the book, allowing the prisoners to speak for themselves, laced with interesting nuggets, humour and dark sarcasm, makes it a compelling read. The emerging dialogue in many ways underscores the sheer absurdity of the state in branding these individuals as "dangerous" or "threats to national security,” when the ground reality is that they are passionate citizens advocating for social justice, equality and human dignity.

In the end, the book makes one think aloud: Do these individuals really need to be subjected to brutal repression because they are feared by the state?