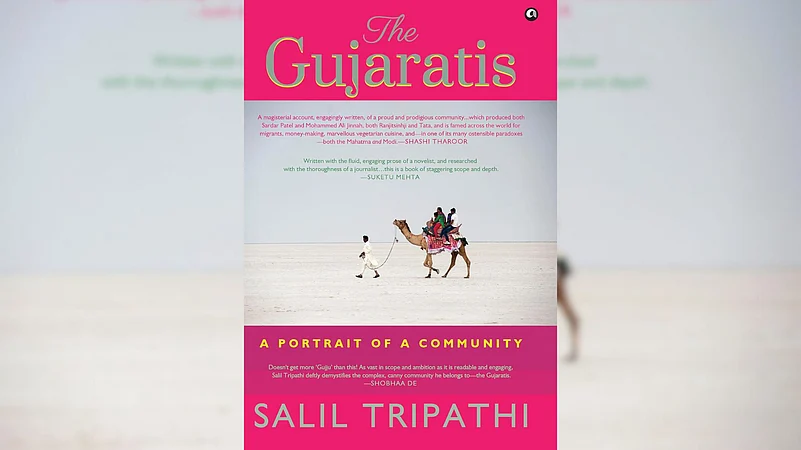

The cover image of the vast expanse of the Rann of Kutch of Salil Tripathi's book, The Gujaratis: A Portrait of a Community, is arresting, providing a touristy gaze. It took Tripathi, an award-winning journalist based in New York, eight years to finish his book, an in-depth account of the economic, cultural, political and social aspects of the community he was born into. The Gujaratis: A Portrait of a Community is a first-person account of his own growing up years and exploration of the Gujarati community. He spent his childhood in South Mumbai, studied abroad, and has been living outside India since 1991. He does add a disclaimer that the book is not meant to be an encyclopedia on the Gujaratis. In the Author's note, he explains that he is using an expansionist definition of who a Gujarati is and is taking ‘the inside looking out and the outside looking in’ view of the Gujarati community.

Tripathi uses the term community which is debatable; since community can be of place, purpose, need, interest, convenience, and identity. He talks about ‘hesitancy and confidence’ in telling his story. While he uses his Gujarati identity, he includes people with one Gujarati parent and those who were brought up by Gujarati parents, not knowing how to read or write Gujarati, and even those who migrated out of India, yet believe in Gujarati identity. The definition of community in its vastness has encompassed Gujaratis of varied classes, castes, religions, regions, and genders. And hence his question, “What kind of Gujarati is more Gujarati?”.

My doctoral work about Gujarati and Marathi-speaking television audiences of Mumbai was undertaken in the early 2000s. Born and brought up in Gujarat, having spent close to three decades in Ahmedabad, and having been part of Mumbai for a little less than three decades, I have experienced the difference between the Gujaratis of Gujarat and the Gujaratis of Mumbai. Due to my work with Mahila Samakhya Gujarat, I had travelled extensively across villages in Gujarat for four-and-a-half years, experiencing the diversity of the Gujaratis of Gujarat. Interestingly, I was not aware about my 'Gujarati' identity until I landed in Bombay, which became Mumbai in due course of time, with VT (Victoria Terminus) becoming CST (Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus). Like Tripathi who moves out of India and writes about Gujarat, I write this review from outside Gujarat.

Tripathi's book operationalises lines by the Parsi poet Adeshar Faramji Khabardar (1881-53) who wrote mainly in Gujarati: “Jya Jya vase ek Gujarati, tya tya sadakal Gujarat, jya jya bolati Gujarati, tya tya Gurjari ni mohlat” (Wherever resides one Gujarati, Gujarat is there forever/Wherever Gujarati is spoken, it's a celebration of the spirit; Gurjari”. Tripathi's extensive labour of love of over 700 pages documents the good, bad and ugly sides of Gujarati culture. He chooses to use language, heritage, culture, and community in an overlapping sense, all of which are nuanced terms. He writes based on his seven extended visits to Gujarat between 2015 and 2018, and the interviews he conducted with people in Gujarat, Maharashtra and beyond. He also references several existing books. In most instances, he identifies people with their real names in his book.

My Maharashtrian colleagues on the university campus told me in my initial years in Mumbai that they had never seen poor Gujaratis. This was a puzzling observation. I recognised that 'Gujjus' (the term used for those speaking Gujarati) of Mumbai became migrants with the formation of the State, yet they had more material resources than the local Maharashtrians. My colleagues' reference to context was Ghatkopar and Mulund (eastern suburbs of Mumbai) where the Gujaratis were mostly rich merchants. I was born after the separation of the States of Gujarat and Maharashtra and Tripathi let me hop on a time machine via his book, which meticulously traces the history of the State.

While The Gujaratis: A Portrait of a Community is a captivating read for Gujaratis and non-Gujaratis alike, it may be more interesting for those having reference to context for the places and people elaborated upon in the book. Tripathi largely addresses middle-aged Gujarati readers interested in knowing about their roots. There is a reference to Tripathi라이브 바카라 son, who was 25 years old when the project was planned, becoming a reason for him to pursue the book.

My doctoral work clearly revealed inter-cultural diversities among the Gujarati and Marathi-speaking television audiences in the last decade of the 20th century. Marathi women worked outside the home and Gujarati women were homemakers. The Gujaratis were a business community and the majority of the Marathis were in the service sector. This book skillfully dissects the intra-cultural variations within the Gujaratis, yet, makes language a marker of cultural identity.

Tripathi used to travel from Mumbai to Nadiad and back during his summer holidays in the seventies. During my travels from Ahmedabad to Navsari in the eighties, I had similar experiences. While he travelled from Mumbai to the north of Gujarat, I travelled from Ahmedabad to the south of Gujarat. The Gujarat of the seventies and the eighties has been well-documented with cultural and political anecdotes in Tripathi's book. He writes engagingly about his encounters with Gujaratis globally, nationally and locally, providing readers a ringside view of the community.

From Gujarati ‘asmita’ as a political project, he takes us through the length and breadth of not only Gujarat but also the world, talking about the 289 communities in Gujarat listed in the 1985 Anthropological Survey of India. He covers the Kapols, Bhatias, Lohanas, Jains, Dalits, Bohras, Memons, Siddis, Khojas, Nagars, Maldharis, and Chetliya Muslims, among others. He helps readers to understand the present through the prism of the past. He tells stories of businesses with ease and explores social taboos without flinching.

This book offers readers glimpses of history and geography, law and literature, cuisines and culture, lineage and lexicon, Lakshmi (money) and Saraswati (education), diamonds and dollars, surrogacy and spiritualism. Tripathi covers spiritual gurus, politicians, media personalities, musicians, photographers, war veterans, film studio owners, poets, artists: the who라이브 바카라 who of the political, economic, and cultural life of Gujarat, while missing a few who may not be known outside Gujarat from where he is locating his writing.

There are recurring references to Nadiad where Tripathi spent his summer vacations, his encounters with Gujaratis during international and local travels, his personal experiences through his parents, and his meetings with well-known Gujarati industrialists. Like his name, 'Salil', which means water in Gujarati, his text takes lucid forms with fluidity.

The book is largely accurate, but in the Prologue, Tripathi chooses dhokla and ganthiya over the more frequent khakhra and thepla. He misses the ‘jalso’ (celebration), a favourite of the Gujaratis, since his gaze is that of a person who grew up in south Mumbai and settled outside India. Though he objects to ‘othering’ throughout the book, readers are ‘othered’ occasionally. Parsis get ‘othered’ subtly. While elaborating about Parsis he uses lines like “Parsis are almost like us”, “We Gujaratis laugh, but rarely about ourselves, Parsis laugh at everyone, including themselves”. I grew up with Parsi neighbours and always knew them as people who are ‘not like us’ though they spoke Gujarati. This perhaps validates Tripathi's lines.

Tripathy takes us through fascinating stories of Singaporean Gujarati childhood, the Indian independence movement, World War II stories, Gujarati NRI motel owners' trajectories, lesbians coming out of the closet, spiritual gurus exploiting their followers, the challenges of running a surrogacy hospital at Anand, and many more. He weaves the specific to the general and the general to the specific. The themes of micro aggression, violence, atrocities, identity, and nationalism reoccur on the pages. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi forms the core of this book.

Tripathi's human rights research background is mirrored throughout the book, which contains his personal views on and concerns about violence. He takes a clear position on the vital need for tolerance, communal harmony, and peace. The pain he feels about the hypocrisy prevailing in day-to-day Gujarati life in our time is articulated well.

While Tripathi's book exposes us to people, places and perspectives, it fails to an extent to tell us about language as a world view or identity. There are references of diversity within the language in terms of lexicon, but not about varied worldviews within Gujarat and Gujaratis. It unifies the singularity of the language, Gujarati. Packed with an impressive amount of original research and scholarship as well as an elaborate list of references covering books, visual resources, social media posts, doctoral theses and research papers, legal citations and reports, and a detailed index, this book is a valuable resource for anyone interested in the diversity and duality of Gujarati culture and the Gujarati language.

(Prof (Dr.) Mira K Desai is a Senior Professor & Head of the University Department of Extension & Communication, SNDTWU, Juhu Campus, Mumbai)