I remember a conversation between two members of my extended family about the hajj, or the pilgrimage to Mecca, when I was a child. One of them, an elderly lady, had just returned from the pilgrimage and the other, a younger male relative, asked her what it felt like. The lady라이브 바카라 eyes lit up and she said that initially she had been very scared, as it went by so fast, but it was great to soar above the clouds and look down at the earth below from the aeroplane. The gentleman, himself a more widely travelled person, jokingly chided her: “Baaji (elder sister or cousin), I meant the destination, the holy city of Mecca, not how you got there!” This was a time when international air travel was just about becoming something more commonplace for the Indian middle class and therefore retained a kind of novelty to it. There were still stories going around about people making the journey by steamer ship.

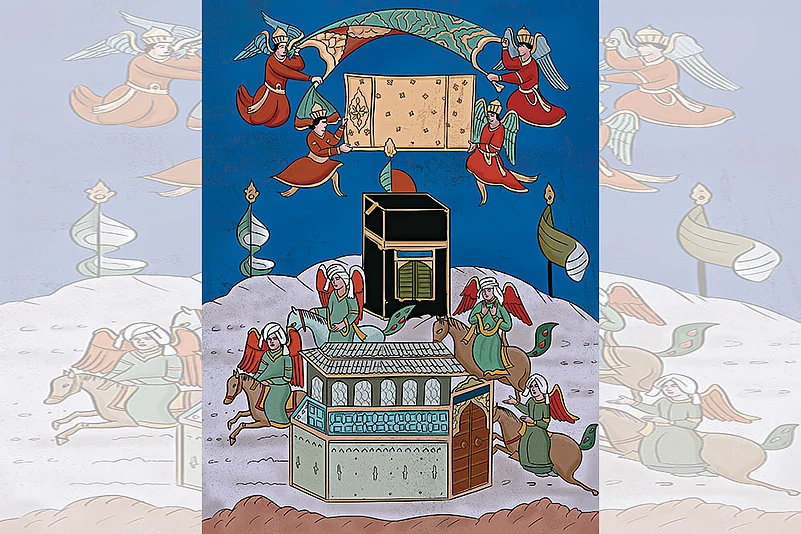

The early experiences of hajj were ones about the great difficulty getting there—of pilgrims traversing the path on foot and on a camel라이브 바카라 back. There were tales of hajj pilgrims being looted on the way by robbers and highwaymen. Today라이브 바카라 experience seems to be much smoother. The city of Mecca itself and the precincts of the Masjid al-Haram or the Grand Mosque that encloses Islam라이브 바카라 holiest site—the Kaaba—have acquired the sheen of capitalism, made possible by the mighty petrodollar wealth of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The current cooling system of the Grand Mosque is one of the largest in the world with an energy consumption reaching 1,55,000 tonnes of refrigeration.

Today, the King of Saudi Arabia is referred to as the Khadim al-Haramain al-Sharifain or the custodian of the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The title originated with the Ottoman rulers when they had territorial jurisdiction over both cities. On the eve of the 1987 hajj pilgrimage, around 400 people were killed in the clashes between mostly Iranian Shia pilgrims, who had organised a protest march, and Saudi security forces. The Iranian pilgrims chanted slogans like “Death to America! Death to the Soviet Union! Death to Israel”, as they brandished portraits of Iran라이브 바카라 spiritual leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The Saudi authorities claimed that no bullets were fired at the demonstrators and that people were trampled to death. Ayatollah Khomeini라이브 바카라 designated successor Ayatollah Ali Montazeri suggested that Muslim leaders should take control of the two holy cities from the Saudi royal family. In 1979, a Sunni fundamentalist group took control of the Grand Mosque and the ensuing siege led to over a hundred members of the group being killed.

Hajj is one of the five obligations incumbent on Muslims, the others being a sincere profession of faith (shahadah); the mandatory prayers, five times a day (salat); fasting during the holy month of Ramadan (sawm); and offering charity to the poor (zakat). The hajj pilgrimage has itself become much more commonplace with the increased possibility and ease of international travel. The lesser pilgrimage, the umra, has become even more commonplace. Unlike the hajj which is done at a fixed time in the Muslim calendar, the umra can be undertaken at any time of the year. Richer members of the conspicuously consuming and jet-setting upper reaches of the Muslim middle classes from across the world are likely to make the umra very frequently. Recently, a friend who I had not particularly associated with spiritual pilgrimages and journeys, shared his experience of the umra and how he made friends with some “London ke laundey” (slightly boisterous London lads) as he called them, who were also on the umra.

The hajj and the umra have become, like many aspects of the world we live in, a part of the larger neo-liberalisation of daily life and the conspicuous consumption of travel.

The hajj and the umra have become, like many aspects of the world we live in today, a part of the larger neo-liberalisation of everyday life and the conspicuous consumption of travel. This has of course been facilitated by the greater accessibility of international travel, but more importantly, by the mobile phone and social media messaging. I have heard more austere and elderly members of my own family express disapproval of the way younger members use mobile phones to click selfies with the religious sites of Mecca and Medina as the background. In these exchanges between elderly members with younger, more confidently and widely travelled ones, there is a clash not just between generational values, but the more austere and simpler form of Islam that older generations tended to uphold, which contrasts with the more consumerist form of religion that younger generations have become inured into. In these times of climate crisis, with the proliferation of often Islamophobic and far-right political establishments ignoring the very reality of climate change, agonised conversations that I have had with friends and family have led to suggestions that it may be important to bring back among Muslims, the frowning upon of israaf-e-bejaa (superfluous consumption beyond what is really needed), which being a simple and austere principle that many Muslims have grown up with.

The ease with which people can make the pilgrimages of the hajj and the umra is certainly something to be welcomed as it allows larger numbers of Muslims to experience the holy cities. In the first week of March this year, it was reported that on one day alone, 5,00,000 umra performers entered the Grand Mosque in Mecca—the highest number ever recorded. What may not be so welcome are the subtleties that many Muslims may miss as a result of the overall commoditisation of the experience. There is an intense level of commercialisation of the holy city of Mecca. There are luxury hotels in close proximity to the Grand Mosque that tower over it and afford stunning views of the Kaaba. This intense rate of building activity is complemented by a tendency within the strict Wahhabi Islam that is followed by the Saudi regime to erase all traces of historical places associated with the Prophet Muhammad and his companions. Wahhabi Islam is very particular about any historical indicator or site that may become the focus of excessive devotion of pilgrims. This is done with a view to avoiding what is considered to be the highest sin in Islam— shirk—which means to pay excessive devotion to any person or entity that may escalate to the level of associating or equating the entity or the person with Allah.

What is lost through the glitz that Mecca has acquired, is the subtlety of the spiritual experience which, after all, is what pilgrims may really be in search of. This may appear and arise in different forms. Take for instance one of the most poignantly portrayed of experiences of the hajj by the famous Black American leader Malcolm X in his autobiography. Upon his arrival in Jeddah before he embarked for Mecca in 1964, Malcolm X noted the camaraderie of the pilgrims at the airport as they ate together: “Everything about the pilgrimage atmosphere accented the Oneness of Man under One God”. When he arrived at the holy city, he noted: “Mecca, when we entered, seemed as ancient as time itself”. As Macolm X was about to complete the hajj pilgrimage, he sat in a tent on Mount Arafat with twenty other Muslims, who asked him what the experience had taught him. He says that his answer surprised them when he said: “The brotherhood! The people of all races, colours, from all over the world coming together as one!”

The hajj pilgrimage with the movement of the large number of pilgrims that it entails, is itself a significant contributor to Saudi revenue and the economy, in fact, forming the second largest share of government revenue after hydrocarbon exports. Saudi Arabia earns $10-15 billion on average in a year from the hajj and $4-5 billion from the umra. As a religious and cultural phenomenon, it is an important component of the wider cosmopolitanism of the Muslim world and this stands in contrast to the kind of Saudi nationalism that the de facto leader, crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, is espousing as part of the wider political and economic reforms that he has undertaken to modernise and reform the Saudi economy and, most importantly, wean it away from its excessive dependence on petroleum exports.

To underline this point about the cosmopolitan nature of the hajj, consider the fact that the travels of the great Ibn Battuta of the 14th century began with the intention of making the hajj pilgrimage. This is how he begins the account of his celebrated travels: “I left Tangier, my birthplace, on Thursday, 2nd Rajab, 725 AH, [the lunar Muslim calendar that corresponds to 14th June 1325], being at that time twenty-two [lunar] years of age, with the intention of making the Pilgrimage to the Holy House [at Mecca] and the Tomb of the Prophet [at Madina]”.

(Views expressed are personal)

Amir Ali teaches at the Centre for Political Studies, JNU, New Delhi

This article is a part of 바카라's March 21, 2025 issue 'The Pilgrim's Progress', which explores the unprecedented upsurge in religious tourism in India. It appeared in print as 'Shopping With God'.