If you can read this, you’re standing too close.

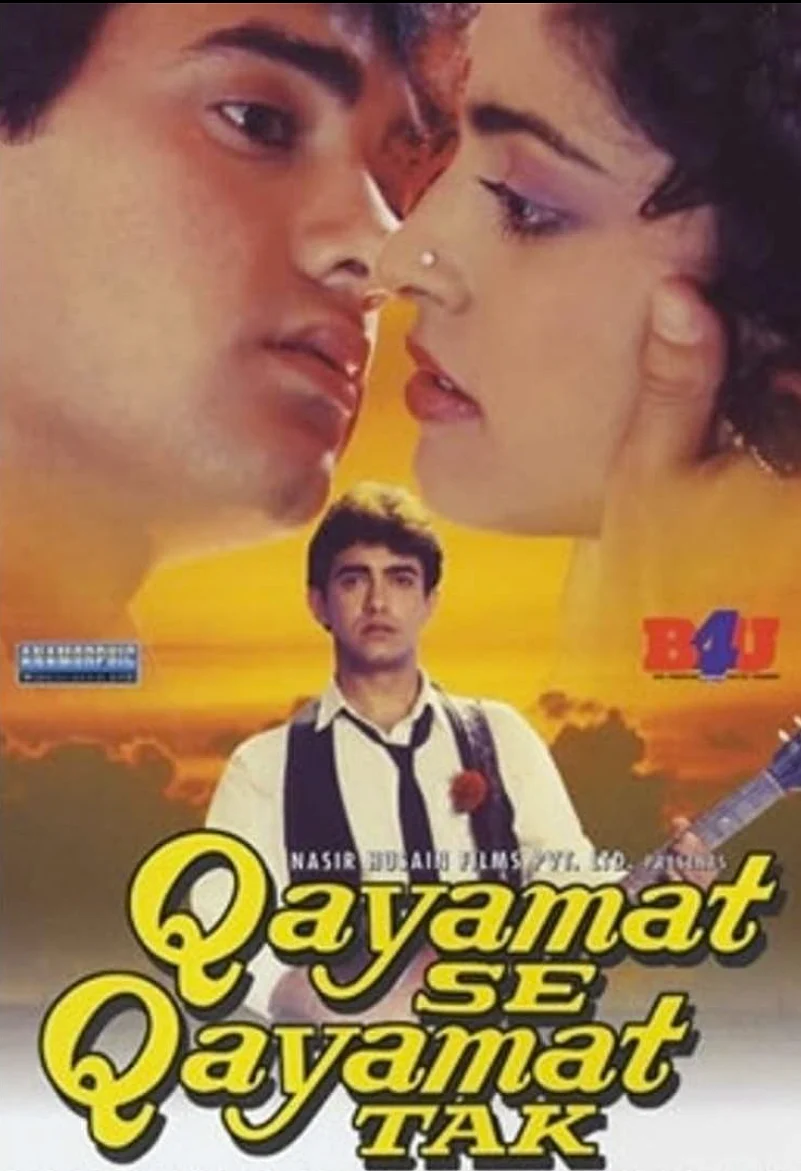

The recent re-release of Qayamat se Qayamat Tak (1988) as part of the Aamir Khan retrospective ‘Cinema ka Jaadugar’ in PVR theatres across the country got me very excited. After being shamed for at least a decade for not having watched one of Hindi cinema라이브 바카라 most successful star launch vehicles, I finally had my chance at redemption. I finally could claim—even one up most of my peers and friends born in the 1990s, who had only seen it on television—that I had watched QSQT ‘the way it was meant to be seen.’

Growing up, I had heard tales of the mania surrounding the film라이브 바카라 release. My father had told me about how he had watched the film three times on opening day, where he would catch a part of the film each time. Considering that my father wasn’t really a cinephile, I wondered what prompted him to do this. On asking him, he would say that his memory is fuzzy about the reason, but the only thing certain was that the cheap tickets allowed him to do so. Considering that all the theatres near where I live are part of some corporate theatre chain, I cannot imagine buying three opening day tickets for a big budget Bollywood film, each ticket costing anywhere between Rs. 300-350. While booking a ticket this time, I encountered a new addition to the PVR app that made me groan. A new “Flexi Show” option allows moviegoers to pay only for the time they watch. In corporate speak, “The system uses AI-powered video analytics to track audience presence and calculate refunds based on when viewers enter and exit the theatre.”

Keeping my frustrations with PVR aside, I told my father that I was going to watch QSQT in theatres and invited him to relive his nostalgia. To my surprise, he immediately agreed, and even adjusted his schedule for the film. On the other hand were some of my peers who warned me, “It라이브 바카라 a typical 80s Bollywood film, so temper your expectations.” While wondering what exactly a typical 80s film is, I entered the theatre shrugging, “Well, at least the songs are excellent.” There were around 10 people in the audience. I thought to myself, “Well, maybe not exactly the way it was meant to be seen, then.”

To my relief, the film began straightaway, without any glossy and loud advertisements. An image of lightning followed by a deep, disembodied voice thundered on screen, “Kya ishq ne samjha hai, Kya husn ne jaana hai, hum khak-nashino ki, thokar mein zamaana hai.” (trans: Has beauty comprehended this and does their love realize, in the footsteps of us lowly lovers, the fate of this world lies) Urdu couplet written by Jigar Moradabadi—a poet who wrote another famous couplet, “Ye Ishq nahi Aasaan” (Love is not easy)—speaks to the power of the everyday over grand structures in defining eras. This opening was the second instance of an unusual presence of Urdu in contemporary film-going experiences. The first was the film being listed as an Urdu film on the PVR app and websites, not Hindi. As it turns out, these unusual things of the apparent past were only the beginning.

An adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, QSQT is a film where a couple pays the price of falling in love despite the admonishing of their feuding families. While fairly formulaic even by Bollywood standards, the film manages to capture the goofiness of awkward meet-cutes, the initial rush of excitement that young love symbolizes, and perhaps most powerfully, the debilitating hold of venom and hate on Indian families. In fact, after the violent prologue— which tells us the origin of the feud—the film remains largely violence-free. There are no scheming villains in the film, only those who are hurting and unwilling to move on. Perhaps, this is why, despite knowing that an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet can only end in tragedy, the film feels like it will end with reconciliation, only to pull the rug out from under you.

While watching the film, I kept waiting for it to turn repetitive or boring. We have, after all, seen other films like these, even as star vehicles a la Bobby (1973). The film definitely felt like an 80s film—the way in which it was shot and acted, and for the attempted rape sequence. But over the course of the film, the “80s movie” tag stared feeling less like a pejorative and more like a specific set of aesthetic choices which, if I may dare to say, felt refreshing. Seeing the rawness of Aamir Khan라이브 바카라 carefree performance as Raj in the deeply affecting “Papa kehte hain”, the innocence yet firmness with which Juhi Chawla라이브 바카라 Rashmi expresses her feelings to Raj, and the bold visual and aural swings that the film takes, put me in a strange state of melancholy. This was precisely the cinema that Aamir Khan famously broke away from with films like Dil Chahta Hai and Lagaan. And yet, here I was, yearning for older forms and idioms of Hindi cinema, when star launches did not necessarily mean compromised storytelling.

In one of the blink-and-you-miss it sequences from QSQT, Raj라이브 바카라 brother asks him to consider telling Rashmi about their family histories. The camera captures Aamir Khan in a mid-shot, so that the audience can just about read what is written on his T-Shirt, “If you can read this, you’re standing too close.” A slight chuckle escaped my lips, as I was reminded of Walter Benjamin라이브 바카라 thesis, in 1935, on what mechanical reproduction does to works of art. How photographs and film are linked to the desire of masses to bring things closer to them, infusing themselves in what they see and experience. Was it nostalgia then—for a certain kind of time—that I was reading into the film? Is this also the case with most re-releases these days, where the labour of good storytelling is outsourced to the past, coming to us as repackaged goods designed for spectatorial performance? All this, while the contemporary popular Hindi film either gets increasingly absorbed into the pits of mediocrity or outright hate-manufacturing?

In some senses, the movie star has always been a figure of capital inflow from film paraphernalia. Even the recent trend of re-releases has mostly been built around individual male stars like Amitabh Bachchan, Dilip Kumar, Dev Anand, Raj Kapoor, and now Aamir Khan. That Film Heritage Foundation is framing film restoration within the language of stardom speaks to Hindi cinema라이브 바카라 overdependence on the star. The star organises film culture to entrench himself as the driver of business in and around the film. And yet, even within those limitations, the star diffuses into something more fleeting—a wisp of the untamed desires and potentialities of masses that explodes on screen. Off late, that quality has all but vanished from the popular Hindi film. 2024 had, for the first time in a long time (barring the COVID years), no releases from any of the Khans—our staple diet of film stardom. The closest we got to a genuine star figure was singer-actor Diljit Dosanjh, as he dominated the media cycle with the release of Amar Singh Chamkila, as well as his provocations and statements during the “Dil-Luminati” world tour. But even he was tamed, it seemed, when a video of his meeting with the Indian Prime Minister was released. This year, with Chhaava, one could argue, that Vicky Kaushal emerged as a major star. But to me, this kind of stardom is not just a realignment of capital but a filmic capitulation, a surrender to structural forces that already dominate the public sphere. This kind of stardom pales in comparison to the other—a more complex figuration.

Maybe the popular Hindi film will find its voice again and reinvent itself. After all,QSQT, along with Tezaab (1988), Ram Lakhan (1989), Tridev (1989), Chandni (1989) and Maine Pyar Kiya (1989) were films that brought audiences back to the theatres, after the failures of quite a few high-profile films in the 80s. Or maybe this is me giving film history too much importance. This is unlike my father, who, when asked post-screening what he remembered from the film from those days, replied, “Nothing much, except the songs. The songs are excellent.”

Piyush Chhabra is a Ph.D Scholar of Cinema Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He works on the entanglements between law and different media forms.