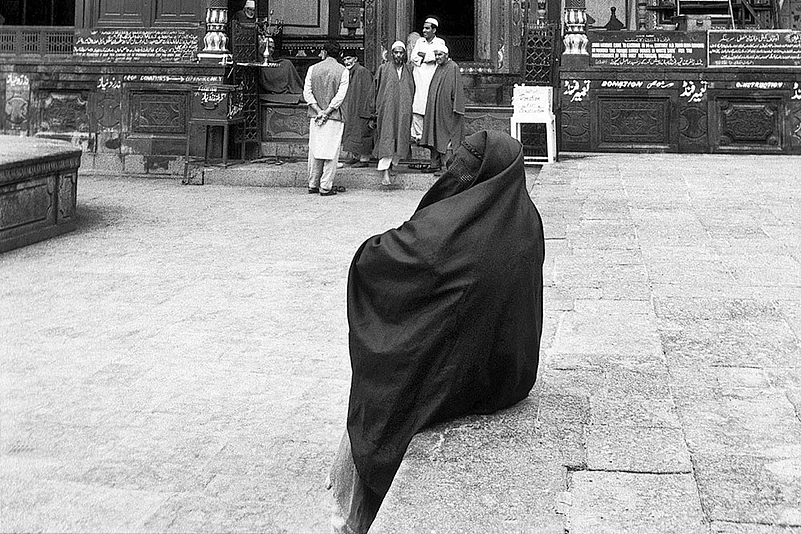

In the hushed courtyard of a dargah in Lucknow, marigolds lie like scattered prayers. A young girl bends to tie a thread at the lattice wall—eyes closed, silently murmuring her negotiation with the divine. Behind her, a weather-worn plaque bears the name of a benefactor long forgotten by official memory, but still whispered in the wind.

Wazeeran Bai.

The name doesn’t appear in textbooks or waqf board archives with any pride. And yet, if you ask the flower-seller at the gate or the old caretaker polishing the brass lamp inside, they’ll tell you she was the one who gave the land. For the shrine. For the well. For the girls’ library next door.

In Delhi, they say that when Gauhar Jaan died, her jewellery box still had receipts of donations made to mosques and women라이브 바카라 clinics in Calcutta. The first Indian voice ever recorded, she was a woman who sang in Hindustani and ironically, gave in silence. In Hyderabad, tales circulate of Rekhti poets—tawaifs who wrote in the voice of women, for women—and funded spaces for literacy in the alleys near Charminar. In Banaras, they remember courtesans who sponsored musicians’ pensions and temple musicians’ meals—Hindu, Muslim, all. But most of these names are not even in footnotes of history. And there are no museums to preserve their memory.

In Islamic tradition, “waqf” is a gesture of permanence—a property removed from private hands and dedicated, eternally, to public good. A permanent pact between wealth and welfare etched in time between the faithful and the divine. Across empires and centuries, it has served as a cornerstone of religious philanthropy, architectural patronage, and community care. The Qur’an does not use the term “waqf”, but the practice has been systematised by the Prophet Muhammad and institutionalised during the Abbasid and Ottoman empires. Jurisprudential schools such as the Hanafi, Maliki, and Shafi’i developed detailed rulings on its form and function. Critically, all schools of Islamic law recognise the capacity of Muslim women to create waqf without any legal barriers to endow their property—whether land, buildings, or movable assets—for sacred or social purposes.

Yet historical record suggests something more complicated than jurisprudential permission. In the Ottoman Empire, women라이브 바카라 waqfiyyas—legal documents establishing waqf—do exist. They number in hundreds across Istanbul, Aleppo, Cairo, and Jerusalem for mosques, fountains, madrasas, and soup kitchens. Notable figures such as Hürrem Sultan, Nurbanu Sultan, and Kösem Sultan were prolific patrons of public works through waqf. In Mughal India, figures like Fatehpuri Begum endowed mosques and associated lands in Delhi, while courtesan-rulers such as Begum Samru funded religious and charitable structures.

Despite this, mainstream Islamic historiography in South Asia has rarely foregrounded women as active waqf-makers. Waqf records swell with names of Nawabs and Khans but identities of Bibis, Bais, and Khatoons either blur behind patriarchal genealogies – husbands, patrons, caretakers—or they simply disappear. This erasure of Muslim women—elite and non-elite, royal and courtesan— reflects a broader discomfort with female piety expressed through property. The pious woman may pray, serve, donate quietly—but to endow? To manage? To claim religious legitimacy through wealth? To register that some of those who were once sold yesterday could also give. That, historically, has threatened the patriarchal logic of both mosque and the State.

In India, waqf imagination of women features her as caretakers of shrines, as donors cloaked in anonymity, as beneficiaries often without a voice in distribution. She was never meant to be remembered as sacred or as wealthy. But to be both and to choose to give—those are acts of perversity, of transgression, of insurgency! She gave when no one asked. Silently. She registered a pact with the divine that bypassed clerics, Qazis, and the tired laws of men. Almost like a prayer that needed no permission.

Her act of giving was rebellion dressed in rose attar. And she gave not just alms, not just time—but land. Property. Permanence. And not to her family or to her lovers, but to the public—to strangers who might never know her name. She gave from the edge of the erasure she saw coming. She gave knowing she would vanish—from ledgers, plaques and historical land records.

Today, long after her name has faded from the records she should have been inscribed in, the State takes a step—overdue, but essential. The amended Waqf Act, tabled in the Rajya Sabha in December 2023—enforced nationally from 2025—introduced a pivotal clause: every Waqf Board must now include at least two Muslim women as members. The provision acknowledges, at least formally, that gender parity in sacred administration is no longer a matter of progressive optics but of legal obligation. In a system where Muslim women have historically been erased from land ledgers as endowers and reduced to passive recipients—of charity, of religious doctrine, of social protection—this amendment suggests a shift toward visibility and participation.

For participation to mean power, it must also restore memory. No national or state-led initiative has documented the historical contributions of women to waqf in India. And yet, archival work by scholars such as Saadia Toor, Ruby Lal, and Gail Minault reveals that Muslim women in colonial and pre-colonial India were far more economically active than the official narrative suggests. Their names may be absent from waqf ledgers, but their intentions echo the spirit of irrevocable, sacred public giving. Will these women at the table now record and register the whispered truths of past? Will they shape educational priorities or be consulted on matters affecting beneficiaries? Will they influence financial disbursement? It is entirely possible—indeed historically likely—that the two women appointed will be chosen not for their independence, but for their alignment with existing patriarchal and other ossified structures within the boards. The amendment stops short of specifying the roles these women members will play.

To rethink waqf as a tool for gender justice, we must ask: where does its wealth flow? State data reveals that women-specific institutions—girls’ madrasas, hostels, health initiatives—receive a negligible share of waqf resources. Yet women and girls comprise a significant portion of India라이브 바카라 most economically vulnerable Muslims. Redirecting waqf revenues to serve their needs is not generosity. It is restitution—a return of the institution to its original purpose: to serve the underserved.

Waqf is not just a religious instrument. It is a civilisational idea—one that sees wealth, once unshackled from self-interest, as capable of becoming eternal. To recognise Muslim women not only as beneficiaries, but as waqifas—givers, architects, patrons—is to restore their rightful place not just in governance, but in history.

The amendment that now places women on waqf boards is being hailed as historic. And history, like patriarchy, has its sleights of hand. Visibility without voice is the oldest mirage of patriarchy. To place two women at the table is not enough. Not when the ink in the room still carries the musk of masculine authorship. Not unless her pen draws from the silence of centuries and redrafts the blueprint of power in the present. Until the physical, metaphysical, and legal architecture of governance bears her handprint, reform remains haunted by the choreography of inclusion.

The reform has begun. The doors have opened. But the question remains: will the keys be handed over—or will women, once again, be left standing at the threshold of the sacred?

(Views expressed are personal)

Shubhrastha Shikha is a political consultant, author, and a speaker across multiple platforms

This article is part of 바카라라이브 바카라 May 01, 2025 issue 'Username Waqf' which looks at the Waqf Amendment Act of 2025, its implications, and how it is perceived by the Muslim community. It appeared in print as 'Of Bibis, Bais, And Khatoons'.