“On 26th January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics, we will have equality and in social and economic life, we will have inequality. In politics, we will be recognising the principle of one man, one vote and one vote, one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man, one value.”

—B. R. Ambedkar, on November 25, 1949 in the Constituent Assembly

The statement of Ambedkar is a challenge to every citizen of the Republic of India and also a stern warning as to how Indians are basically leading a life of contradictions. Contradictions exist and even after Amrit Kaal (75 years), they have become stronger both politically and socially. Representation is part of inclusive democracy. However, contradictions existing in social thinking about the nation and nationalism are embedded realities that the citizens are deeply engrossed in guarding. Showcasing the past is also part of safely guarding the interests and going against the inclusive democracy the nation aspires to. These days, the Indic knowledge system is being advocated by the government and a lot of noise is being created around the ideas constantly becoming part of the cultural hegemony of belief in the mythic. The Rational Indic knowledge system does not become part of advocacy. India is a mythic society that believes in its mythic traditions as historical realities. Such a realisation has gone in showcasing museum representations and dissemination of its history by passing archaeological and material culture.

The past is not narrated as part of contradictions and conflicts existing in societies, but a glory that needs to be revived in replications, duplications, a perfect mimesis of the spectre of Brahmanical cultural nationalism that emerged since the colonial period and nurtured by the political parties in power impeccably. Thus, the Sanskritic Indic past gets recycled all the time to create a consciousness of senselessness among the masses who are ghettoised by myths.

The Constitution of India empowers its citizens to adopt and advocate scientific rationality, but in reality it is systemically bypassed to nurture blind faith and belief systems. For example, a professor of physics gets up in the morning and pours water to the sun despite knowing the fact that water will never reach the sun, a fantastic example of ‘protected ignorance’. Thus, knowledge produced in India has to be judged by whether it is aimed at dismantling ignorance or guarding ignorance.

Sanskritists, right from colonial times and revivalism, have a strong belief that their Sanskritic textual tradition is great to an extent in the belief that whatever is described and mentioned in the Vedas is a true testament of the past. In his article published in a book, “India: Historical Beginnings and the Concept of Aryan”, Madhav Deshpande elucidated the historiography of Aryans and observed that scholars such as Narayan B Pavagee wrote in his book in Marathi “Bhāratiya Sāmrājya”, Volume 2, that Aryans did not come from outside India and further argued that “the Aryans spread across the world from the Āryāvartic home and that Sanskrit was the mother of all the languages of the world”.

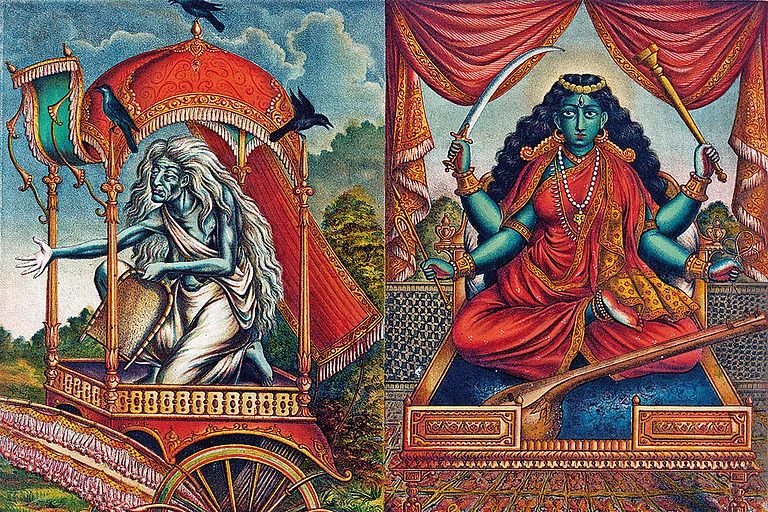

The idea of a common Indo-European language became the hallmark of the dissemination of the language itself, bypassing other historical evidence. A well-known archaeologist, S. R. Rao, while delivering lectures on the Lothal script and the decipherment of the Indus script, declared that the Rig Vedic hymns are inscribed on the seals of the Harappan culture. Another example would be the seal depicting the seated human figure surrounded by the animals that gets the nomenclature “Pashupati Shiva”, and on the other hand, archaeologist Shubhangana Atre identifies it as female deity in her seminal book “Archetypal Mother: A Systemic Approach to Harappan Religion”. But the proposed identification as “female figure” by Atre does not become part of analysis as well as showcasing the seal figurine.

Harappa and Mohenjo-daro have gone to Pakistan, and India has no great Indus site archaeologically as rich as Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. Though many Indus sites were discovered afterwards in India, mainly in the states of Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Gujarat, the nomenclature of Indus-Sarasvati civilisation gets advocated by R. N. Mishra and S. P. Gupta. The river Sarasvati is supposed to be an important river and in its valley, Harappan sites are located on the Indian side. Nevertheless, we are yet to prove which river is “Sarasvati” in Haryana and Rajasthan. Haryana became a hotbed of archaeological expeditions showcasing the Rig Vedic civilisation. It is an apt example of the politics of representation. How the practise of politics induces the culture of myth in its citizens by advocating “protected ignorance”.

The Marxist brand of historians in India claimed that they are the ones who are writing scientific and professional history. The Sanskritists are thickly connected with their deva-bhasha. But is there a tacit understanding that exists between the two? Instead of exploring the answer to the question, it should be explored as a riddle. The claimed scientific Marxist historians emphasised on the archaeological evidence and there should be a correlation between the archaeological material and the textual/literary sources. When these Marxists historians write on the ancient past, they do not question the nomenclature of the Vedic Civilisation.

A civilisation is generally understood as a state of advancement in its social and cultural developments. Neither do the narratives in the Rig Veda fulfil the criteria nor is there a material culture that will corroborate the same. Despite the absence of archaeological evidence, the Marxists have written on Vedic Civilisation, which basically originates from their own belief or the mānyatā (accepted belief).

A Sanskritik example would be “Gitā Rahsya” by a well-known Brahmin nationalist Lokmanya Tilak. The political party in power had named its made in India DC electric locomotive WCM 5 as “Lokmanya” running on the erstwhile DC section of the Indian Railways in Central Railway라이브 바카라 Mumbai division. Both the brands of historians get duly placed by the political outfits of post-independent governments in power. One wonders as to where the archaeological evidence is? Late Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India M. N. Deshpande, in a personal conversation, remarked that the “Rig Veda is a ritualistic text and to excavate history in it is highly problematic”. The quest for Vedic Civilisation is a dream project of the caste-Hindus in India directed by the syndrome of Brahmanical cultural nationalism and the homogeneity of tradition. Likewise, the anti-Brahmanical historical reconstruction eulogises king Bali and advocates king Bali as a historical reality. They fail to prove the date or area of rule of king Bali. King Bali is a figure of Vaishnava myth, thus both dwell and argue on mythic tradition.

The origin and development of the language is another case to be looked into. The mānyatā has become the biggest guiding principle rather than the hard evidence coming from archaeology. The earliest known example of language in India is Pali and Prakrit recorded in third century BC inscriptions. We do not have any evidence to prove the so-called ancient Sanskrit. Nevertheless, the term cchanda bhashā is mentioned in the Buddhist text that provides a hint of the existence of some archaic language. Archaeological findings from Tamil Nadu are also busting certain mythic construction of the āryavarat (area of north India).

Linguistic studies on the Vedas are showing the nature of vocabulary being carried out in the areas of Pakistan and the use of such words by tribes. This aspect is again explained by Deshpande. Therefore, the politics of representation is to be understood from the politics of homogeneity of tradition as well as the power of hegemonic control of the caste-Hindus.

In religious worshiping practices, the textual record existing in the Buddhist text Chullaniddessa is an interesting pointer where there is no mention of Shiva and Vishnu, clearly indicating that their worship is a post-Buddhist advocacy. The trampling images are not explained in its historical conflict in the museum narrations. Their narrative assimilations are in tune with what the caste-Hindu mindset would like to read. The mythic as historical reality has generated a euphoria of hate, anger and violence in modern day democracy where the ideal of scientific rationality is totally set aside.

While tracing the religious icons and their developments, all the time, the quest is to relate everything to the Brahmanical tradition as if it was the only reality of the historical past. The surveys in colonial India show that multiple deities were being worshipped by various social groups, including the castes and tribes that had no connections with the Brahmanical religious systems. In medieval Madhya Pradesh, there are several images of female deities found with inscriptions and their names do not become part of the Brahmanical worshiping practices.

In order to club them with the Brahmanical system, they are showcased as female divine beings under the umbrella of mother goddess worship of the Brahminical society. And the Sanskritist would like to explore the sahastranāmstrota (thousand names) found in various Sanskrit texts. Many Sanskrit texts were also revised during the Mughal times and the colonial times. There are many examples to prove such narratives, and they are still taught as part of deva-vāni, the language of the divine. Their representation is motivational to inculcate false pride, a constant process to be part of “protected ignorance”.

(Views expressed are personal)

Y. S. Alone is professor in Visual Studies In School Of Arts And Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

(This appeared in the print as 'Circumstancial Evidence')